by Dave Segal

“The intent [with my music] is to get to a point where people listen but aren't sure how they got to this place.”

American producer Seth Horvitz's transition from Sutekh to Rrose represents a subtle yet monumental occurrence in electronic music. As Sutekh, Horvitz created heady, spare techno and skewed, funky IDM (see also his Pigeon Funk side project with Kit Clayton and Safety Scissors for the latter style). The Sutekh years—1997 to 2010—resulted in a large, respected catalog with releases on Force Inc., M-nus, Soul Jazz, Orac, Plug Research, and his own label Context.

Without question, Sutekh had name recognition and had risen to festival-playing status, but the endeavor had reached a logical end. For as rigorous and cerebral as Sutekh's output was, it never quite attained the sublime. From a club DJ's perspective, the tracks were more warm-up material than peak-time weaponry, although “Dirty Needles” from 1998's Influenza EP approaches anthem status. And On Bach (2010) is an experimental-techno record that foreshadows some of Rrose's explorations of chilling atmospheres and pointillistic textures. Oddly, it's Sutekh's best, most adventurous album, as Horvitz loosens the structural reins and goes out on several mad limbs timbrally. “The Last Hour” is a fierce organ drone that reflects Horvitz's time spent studying with master maximalist composer/keyboardist Charlemagne Palestine. (They released the collaborative LP The Goldennn Meeenn + Sheenn in 2019.)

“I was kind of flailing for a direction,” Horvitz says about Sutekh's last days. “I was trying a lot of different things. I was trying to be influenced by all the different music that I love. I have really broad taste in music, and I was trying to incorporate it all and it become somewhat of a mess. I kind of lost focus from this root in techno. Then I got tired of techno and wanted to try other things, but I didn't really find the place to go. So the transition point was going back to school and studying at Mills for two years and getting my Master's degree.”

Horvitz's Mills experience and subsequent encounter there with experimental musician Bob Ostertag convinced him that it was time to move into a new musical direction under a different name: Rrose. Their remix project, heard on 2011's Motormouth Variations, launched Horvitz into deeper, darker techno realms. The wildly percolating and bizarrely textured “Arms And Legs [variation one]” serves as a perfect merger of the two artists' skills. And while he doesn't have any desire to revive Sutekh, Horvitz—who played the first Mutek festival in 2000—did a DJ set as Sutekh a few years ago, and enjoyed it. But for the foreseeable future, Rrose remains Horvitz's primary focus. Which is understandable, as Rrose reigns as one of the planet's most riveting techno producers.

Rrose's ascent began with the Primary Evidence and Merchant Of Salt EPs that British label Sandwell District released in 2011. They established the severe, mesmerizing techno and remorseless, industrial atmospheres that have become Rrose hallmarks. “Waterfall” from the latter record set the bar high for trance-inducing transcendence within a technoise framework. It's Rrose's greatest and most psychedelic track, but Horvitz is actually most proud of the 2019 LP Hymn To Moisture (like most Rrose releases, it's on Horvitz's Eaux imprint). “It felt like a culmination of many years of doing this project. It's always a challenge to create something that feels really cohesive beyond just a longer collection of tracks, which I think happens a lot, especially in techno. I embrace the challenge of trying to create something that feel like one piece where all the tracks belong together and support each other and tell a different story from the EPs.”

With its variations on subtle rhythmic hypnosis and textural otherworldliness, Hymn To Moisture achieves rarefied effects without relying on the crutch of melody. Rather, Rrose creates tension and drama through gradual ebbs and flows of microtonal sediments. One outlier, “Horizon,” is as cosmic as anything by New Age genius JD Emmanuel.

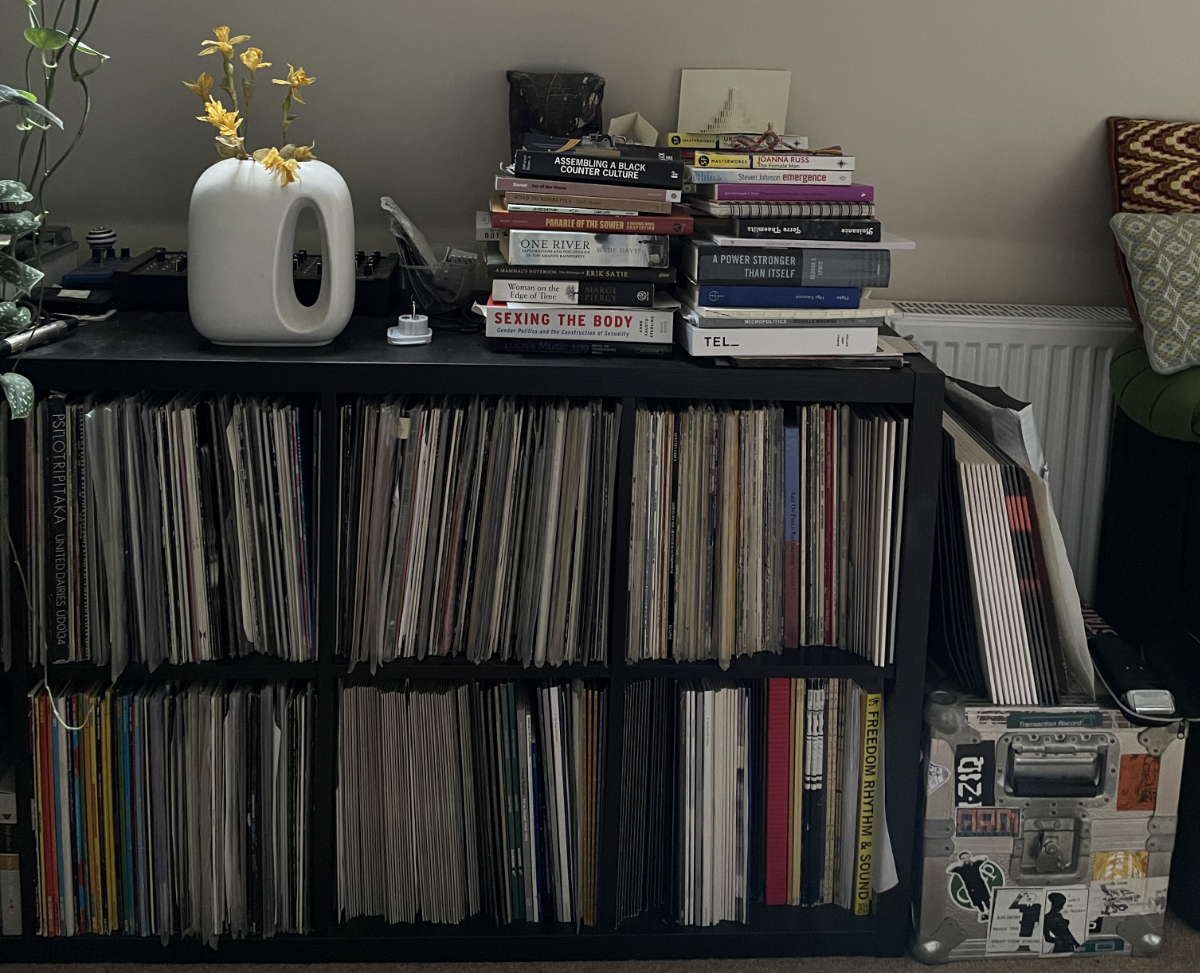

Horvitz got exposed to microtonal music while DJing at UC Berkeley's KALX radio station from the early '90s to late '90s and from hitting Bay Area record stores every week. He picked the brains of KALX DJs and spent many late nights browsing the station's abundant vinyl library. Through some friends at Mills College, Horvitz got to know the work of experimental composer Pauline Oliveros, who was teaching there at the time.

“What attracts me to this idea of microtonal music is partly the way it plays with our perceptions and the way it gets away from the typical emotional structures that are in so much tonal music we listen to.

[I]t places your focus firmly on the sound and what the sound is doing to you in almost a physical sense more than an emotional sense.

Of course they're related. But the focus is more on perception of the physical response to the sound itself, rather than telling a narrative or expressing emotions.”

Going back even further to Horvitz's earliest interest in electronic music, he can trace it to the feeling as a listener that “anything is possible with electronic music, and any sound is possible. Later on I realized that almost any sound is possible with acoustic instruments, as well. So it's a different palette. But the possibilities are a little more diverse in generating electronic sounds, as far as making sounds that we've never heard before.”

After phases of liking band-based music such as punk, goth, indie-rock, and industrial, Horvitz discovered early-'90s dance music and its attendant culture. “The idea that I could just get a couple of pieces of random equipment and make electronic music was also exciting.” He cites two formative discoveries as a fledgling DJ in the early '90s: Aphex Twin's Selected Ambient Works 85-92 and Detroit techno renegades Underground Resistance. “DJ Jonah Sharp [aka Spacetime Continuum] was playing in this chillout room and he had both [Aphex Twin] records on the turntable, and you could see the logo. This was 1992, maybe early '93. I was mesmerized by these logos. I had no idea what it was. Then I actually discovered that record... somebody had brought it into the radio station at Berkeley where I was DJing. That was a real epiphany.” As for UR, Horvitz was enthralled by “the whole mythology around that—the fact that you didn't know who was making the records and it had this political undercurrent to it were exciting to me.”

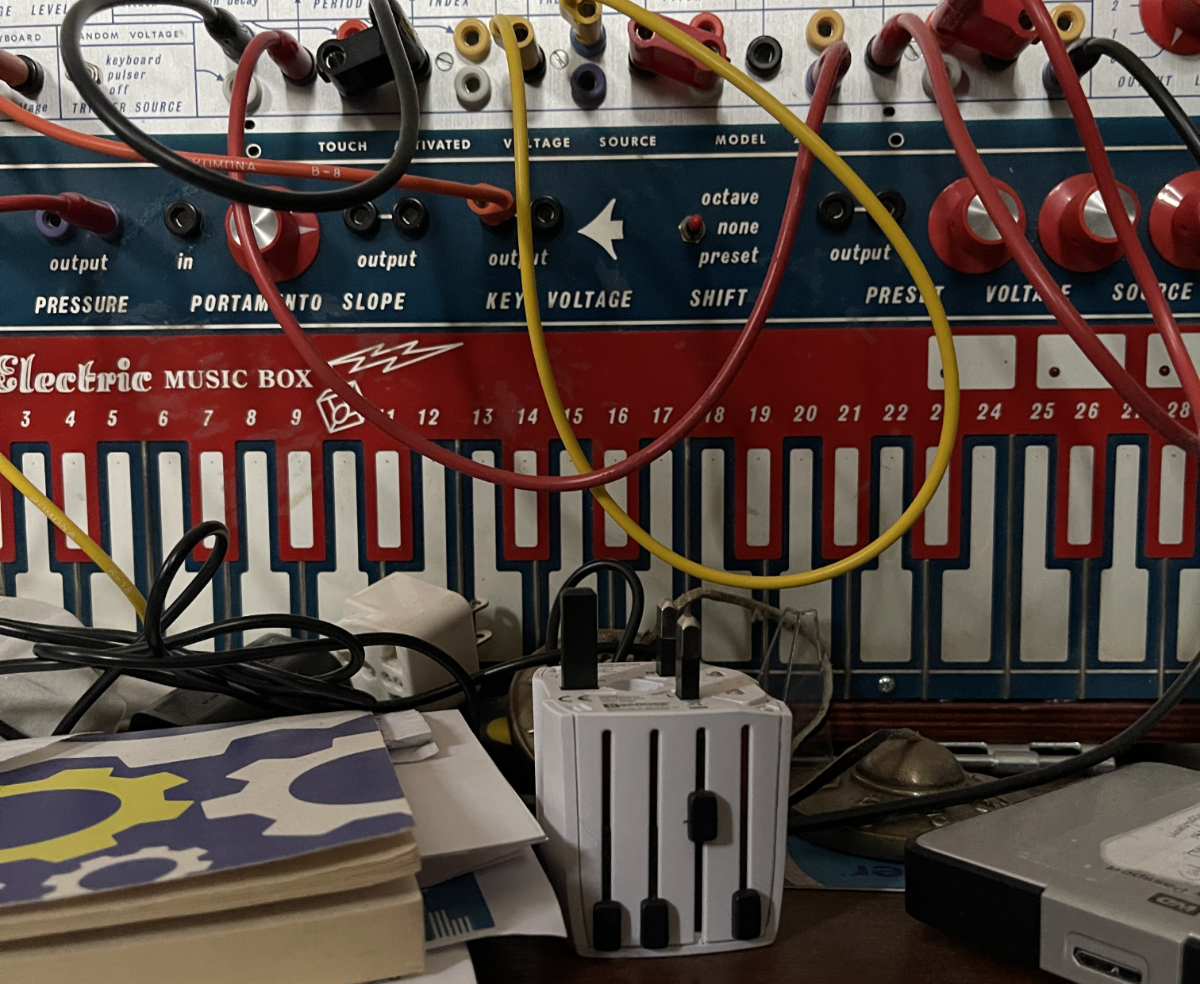

In a 2014 interview with Secret Thirteen, Horvitz said, “I like hardware synths and use them sometimes, but I'm generally happier with the final result when I can control everything in the computer.” He says that that's still the case, “but those things can kind of work together. I have a couple of analog synths, but I don't connect my studio in this professional way, where everything is through a patch bay and into a mixing console and synced up with all the proper equipment so you can run everything together at the same time, synced with the computer.

“My method of working is much simpler. If I'm going to use a synth, like a Buchla Easel—which is partly what inspired [Madrona Labs'] Aalto synth, which I use a lot—I will sit with that synth and play it for a few hours and record stuff that I like with it. I use that as the inspiration for building a track around it. Sometimes I just use the sounds of the Buchla, maybe do a little more with it in the computer, and that's that. I just focus on one synth and see what I can come up with. I let that be the seed that generates other material.”

Horvitz's preferred software for production is Ableton Live, after years of using Logic, but hardware plays an important role in his productions. “I use all of the Madrona Labs synths, but Aalto is the one I use the most. I do like them all and have found uses for all of them in my tracks. The only other gear that I have around is the Buchla Easel and Lyra, which is made by Soma Labs. It's fun—it's a feedback-noise machine, basically.

“I have a lot of recordings I've made from a couple of residencies I'd done, where I had access to Serge Modular System, ARP2500, this kind of stuff. So I tap on these archives of recordings I've made in a couple of residencies in the Netherlands and in Stockholm.”

Like many of the best minimal-techno artists, Rrose avoids blatant emotional signifiers in their work. It's a major part of music to inspire emotions in listeners, but Rrose has decided to de-emphasize that. “I wouldn't say that I've eliminated it, but I'm very aware of it and I try to avoid it. When I made music as Sutekh, I didn't really avoid it. I played with it a lot more. So it was more of a subversive and playful attempt to use tonal language.

“When I started the Rrose project, I made a conscious decision that I was going to stay away from composing melodies, for the most part, and put the focus on the sound. It was interesting because I started trying to make melodic music on my own, and then I became obsessed with learning about it, studying piano, studying jazz and classical music. I wrapped my head around all that theory and then went to Mills College. After learning it all and knowing it, I decided to not use it. I have so much reverence for classical composers and jazz musicians and the way they use the tonal language. One of the reasons I decided not to use it is because I feel like I don't have something important to say in that world that hasn't already been said much better.

“Staying away from that and going into these areas that potentially have shorter history and maybe fewer avenues explored. Applying these non-tonal ideas to techno has a lot of potential and I've been able to make more of a contribution in that area.”

What, if anything, does Horvitz view as the purpose of techno? Does he anticipate that certain people in certain clubs are going to be on hallucinogens and therefore is he trying to enhance that experience? “Ideally, I would like to give someone the same experience as being on a hallucinogen without having to be on one of those,” Horvitz says, laughing. “I don't think I ever quite get there. It's kind of this idea that if you take hallucinogens, you can go on a fast track to some form of enlightenment. But you're never going to be enlightened because you're taking the shortcut. The real way to get there would be to meditate for decades.

“Ideally, the purpose is to create a meditative space for the dancer or listener. I want the listener to experience something that feels like a profound meditation. I think that that can be accomplished through dance, as well. Which is why I get really annoyed when I'm playing for a crowd of people who are all talking. Sometimes people are really social and seem to be really enjoying it and dancing, too. I don't want to get too angry when that happens, but my ideal audience is in a real dark, foggy black box where you can tell everyone is in the zone for the whole set. I want them to have a meditative experience... hopefully, not too specific. Meditation, but the standard way to meditate would be with silence. The idea is to experience whatever is happening in your mind. I hope to have something similarly open-ended.

“Of course, there's an entertaining aspect: People go to dance and they hear this music and it gets your adrenaline going and stimulates all kinds of other things. But I wanted to have some relationship to this meditative state.”

Meditative states also are manifested by Horvitz's excellent collaboration with Luca “Lucy” Mortellaro, known as Lotus Eater. Compared to Horvitz's makeshift home-studio setup, Mortellaro has a big modular rig and patches everything properly. “It's fun to work in someone else's space that has a whole different setup. It ends up being much more spontaneous, especially on the most recent album [Plasma]. We worked really fast on it. The first one [Desatura] took a little longer, compared to how I work on Rrose stuff, where I comb over every detail and revisit things.

“[Lotus Eater is] much more spontaneous and improvisational. It's fun to work that way. It's almost more limited in the sound sources approach than Rrose. We don't use melodies and chords, but we also focus on noise and feedback as central sound sources.” Lotus Eater's music carries a strain of dread similar to that of Throbbing Gristle and Les Vampyrettes. Plasma (Stroboscopic Artefacts, 2022), is a solarized palimpsest of minimal techno, an infernal phantasm of techno's subliminal pulses, a reduction to molecular activity, beats and textures composted into charcoal dust.

While Lotus Eater is anything but formulaic, dance music relies heavily on formulas. Rrose sometimes defaults to certain production techniques or tropes in order to satisfy DJs and dancers, but never in obvious ways. “There are times when I use methods that I know might be slightly manipulative or might achieve a certain effect. But I want it to creep up on people in a way that still feels natural. I don't want to surprise people in the way that I may have done as Sutekh, where I wanted to jar people—at least in the later years of that project. [With Rrose], I want to do something more seductive, like bring people to that point of euphoria, but in a mysterious way, so they're not sure how they got there.

“I have certain working methods that can achieve certain effects, but I try to keep them evolving.” Rrose has put those methods to powerful use on their next two releases on Eaux: the Tulip Space EP (out in February) and the Please Touch album (likely out in May). Tulip Space contains some of Rrose's most slamming dance-floor fillers and weirdest abstract explorations while Please Touch delves more intensely into Rrose's well of hallucinogenic textures and disorienting implied rhythms. Also, a slew of Rrose remixes loom on the horizon for 2023, including those for Pole, JK Flesh (aka Justin Broadrick), Luigi Tozzi, Dutch techno duo Abstract Division, and others.

“The intent [with my music] is to get to a point where people listen but aren't sure how they got to this place. Still, it feels like it's grabbing you and taking you somewhere unexpected, but drawing you in in this immersive way.”